Remembering Maidan - The New Yorker (2014)

By the time Davide Monteleone and I arrived in Kiev last month, the Maidan had become a kind of living museum, an open-air theatre of dramatic but unfinished political and social change. Behind the barricades—made of paving stones, or chairs, or the carcasses of cars—people had built makeshift altars, with votive candles, incense, and framed pictures, to commemorate killed protesters where they had fallen. There was fresh-cut firewood stacked up to fend off the lingering winter; there were self-organized encampments, complete with night patrols, stoves, and tents; there were soup kitchens open to anyone who was hungry.

Each day, Monteleone spent hours documenting the everyday iconography of the revolution. For me, it was all new, but he had been there before, during the murderous days in February, when government snipers had killed a hundred protesters in the square. That outrage had helped lead to the ouster of President Viktor Yanukovych. But, for the protesters, the moment of freedom that followed had been swiftly eclipsed by Vladimir Putin’s takeover of Crimea, the creeping destabilization of eastern Ukraine, and the buildup of Russian troops on the border. Invigorated by their accomplishment but frozen by uncertainty, the protesters had stayed where they were—and so the Maidan was a place in limbo, the embodiment of a country that may or may not have an independent future.

The physical space of the Maidan had accumulated meaning for those who had fought there, and who now grieved for their dead comrades. In lieu of full sovereignty, the revolutionaries seemed determined to retain the one place where they had managed to assert power. Blood had been shed there, and so it was now sacred territory; sacred, too, were the objects within it, no less than the icons in the ancient hilltop churches that surround the square.

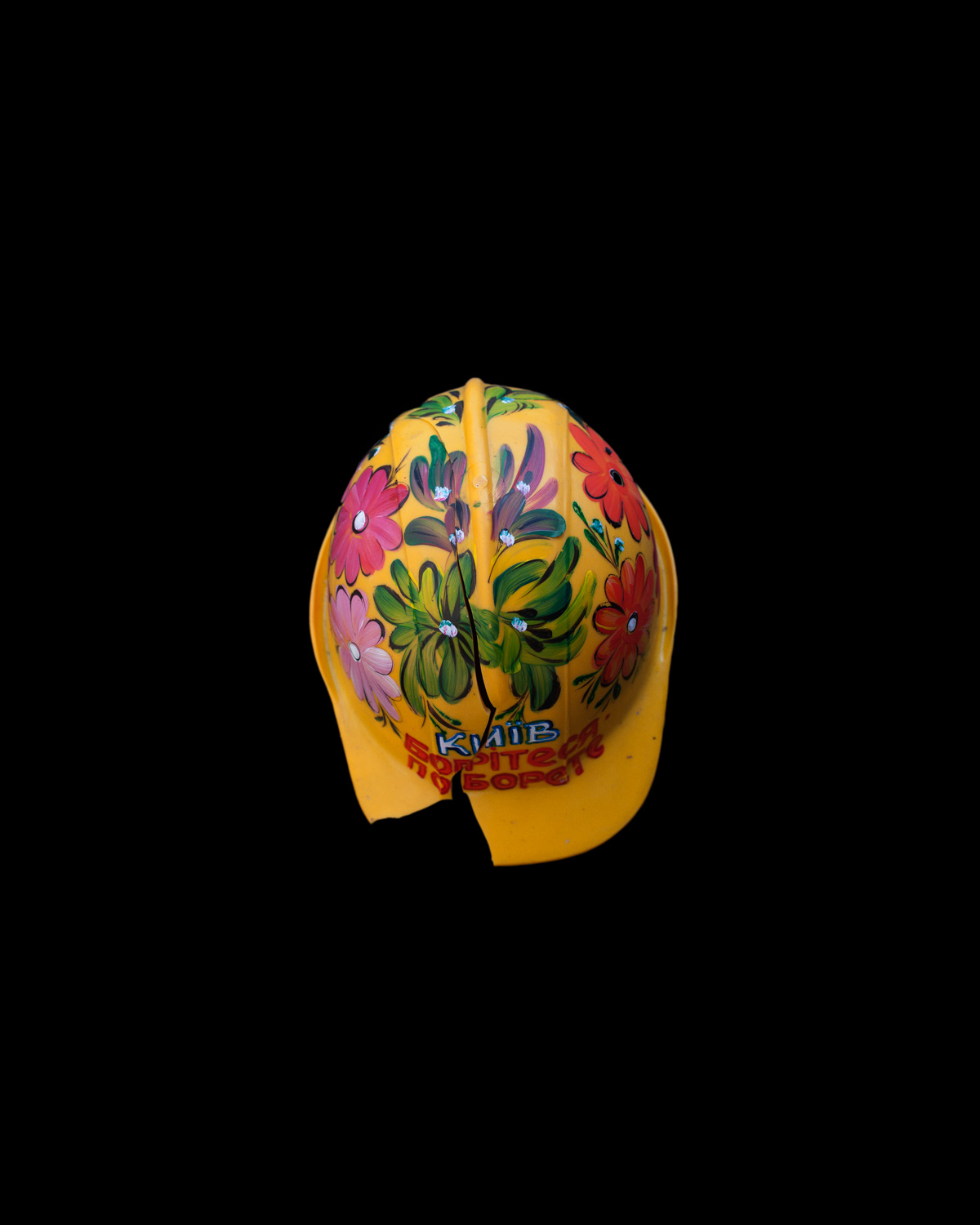

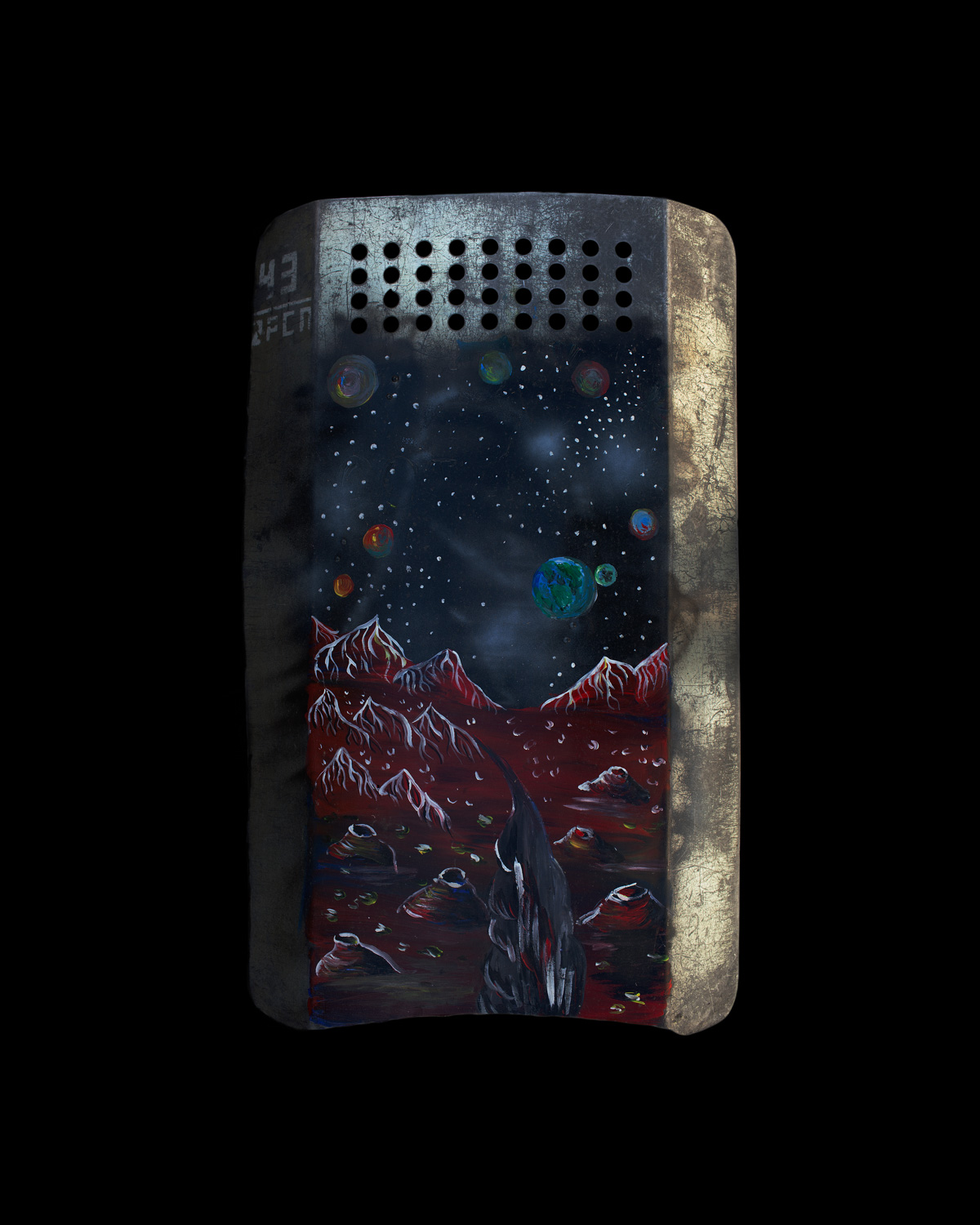

Monteleone’s treatment of the objects of the Maidan—a traditionally patterned scarf, a gas mask, a wooden bat, a hand-painted yellow hard hat—vividly captures that sacred quality. He photographed them at the height of their devotional importance, preserving an extraordinary moment that, like the revolution itself, one suspects, cannot be maintained forever.

Jon Lee Anderson, The New Yorker May 1, 2014

Editor: Whitney Johnson

Writer: Jon Lee Anderson