Red Thistle (2007 - 2011)

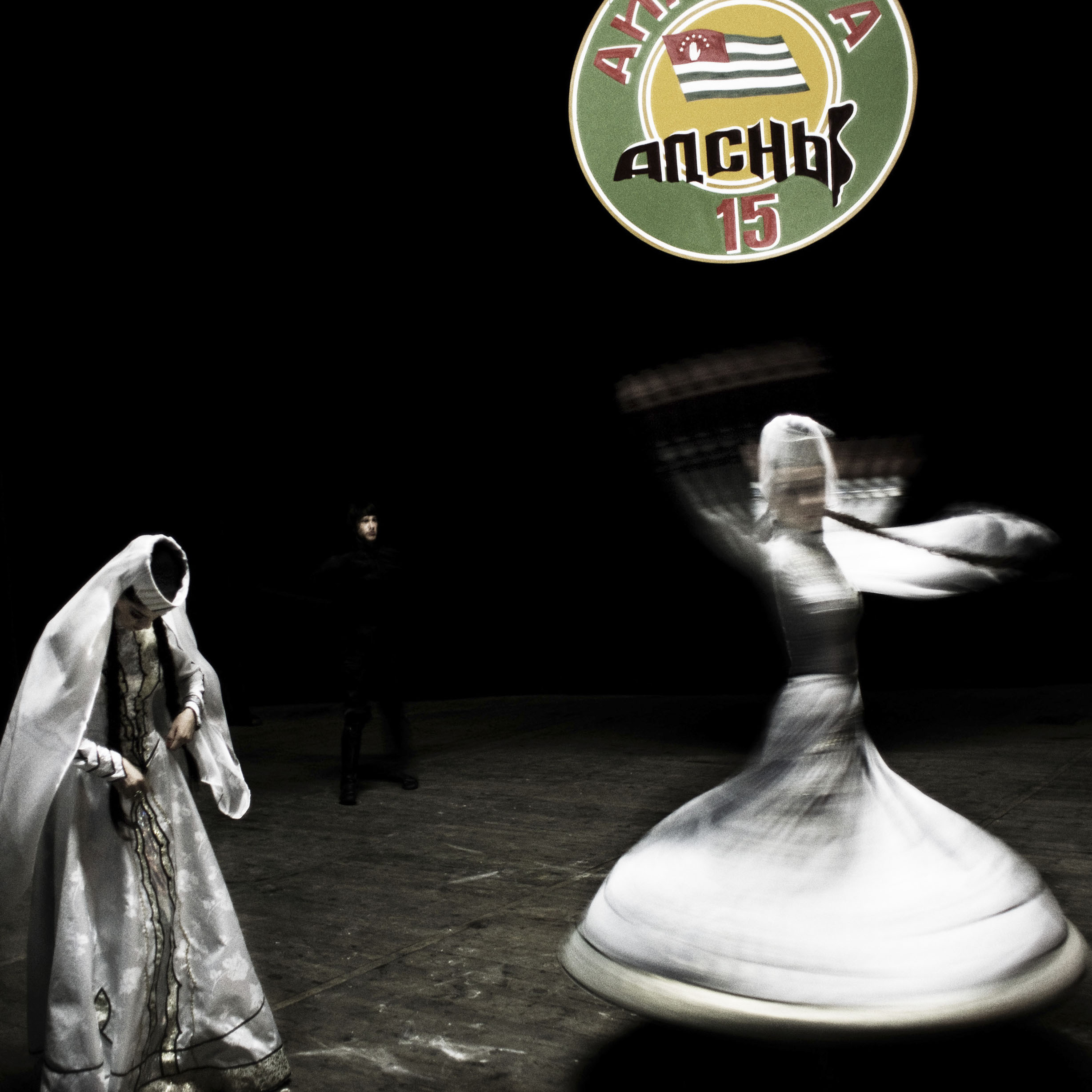

Russia to the edges of the Empire, where Europe becomes Asia, and the birch trees give way to redwoods. The mountain range stretching from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea traces the restless, misunderstood mosaic of the Northern Caucasus, which features in the media predominanty when the endless sporadic wars turn into massacres or genocides. In this inaccessible and inhospitable land, enclosed between two seas, Monteleone has found his theme. A scrupulous narrator, he follows the line drawn by “concerned photography”, and by linking images he constructs a narrative of places and people. In a geographic area as large and rugged as this, the morphology disappears into the fragments of a photograph formed in the perfect square of the medium format: it is forced to share the vision of the author, with no possibility of escape. The desire to tell a story is clear, far from being left to chance, there is a perfect coherence and continuity. And it’s not a coincidence that the work is shot mainly on film: the moment that the shutter is released is distinct from the moment of selection, dilating the need for narrative and releasing it from a sense of urgency to allow it to follow the pace of the journey. Meticulous, attentive to detail and interiors, Monteleone opens his vision to the landscape allowing natural light to define the nuances of color and the changing seasons. An invisible presence inside the houses, he describes a private world and alternates it with the vision of a scarred and desolate landscape, in a balanced dialogue between the individual and his environment. The photographer knows that it is not enough just to travel for miles, it is necessary to have a centre from which to explore; he goes to Grozny and, over a three year period, in addition to Chechnya, he travels to South and North Ossetia, Abkhazia, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachay-Cherkessia. He lives in the places he talks about, interested in the people, he learns to understand their words and their behavior. Each image in this book contains a complex story in which the photographer plays the difficult role of being a witness of events and the guardian of memory, weaving together the stories of the Caucasus and the stories of these men and women. In the best of cases, when an artist photographs he is searching for himself. Witnessing events, he digs into his own feelings. That is why the work is not just a fresco evoking the political and social nature of conflicts and their dramatic consequences. He goes further, achieving a powerful lyricism through his ability to evoke, and to show more closely, a painful world, never just simply chronicling it or describing the geography. And so, the reverence of the author can be seen in the portraits of women – resigned protagonists – in the images of tombstones and shrines as well as in the buildings destroyed by the explosions of yesterday or today, and the memory of the war finds its place between private tragedy and collective drama. As with every story, that of the Caucasus is also full of puzzles, of questions without an answer. That is why from time to time, open to doubt, Monteleone lets himself give way to surreal images, which are able to hold on to the small mysteries, and to disrupt the conscious balance with which he has built this work. He returns to the magical power of photography, which doesn’t confirm things, but continually proposes new questions.