A people’s friendship - Asia Society (2016)

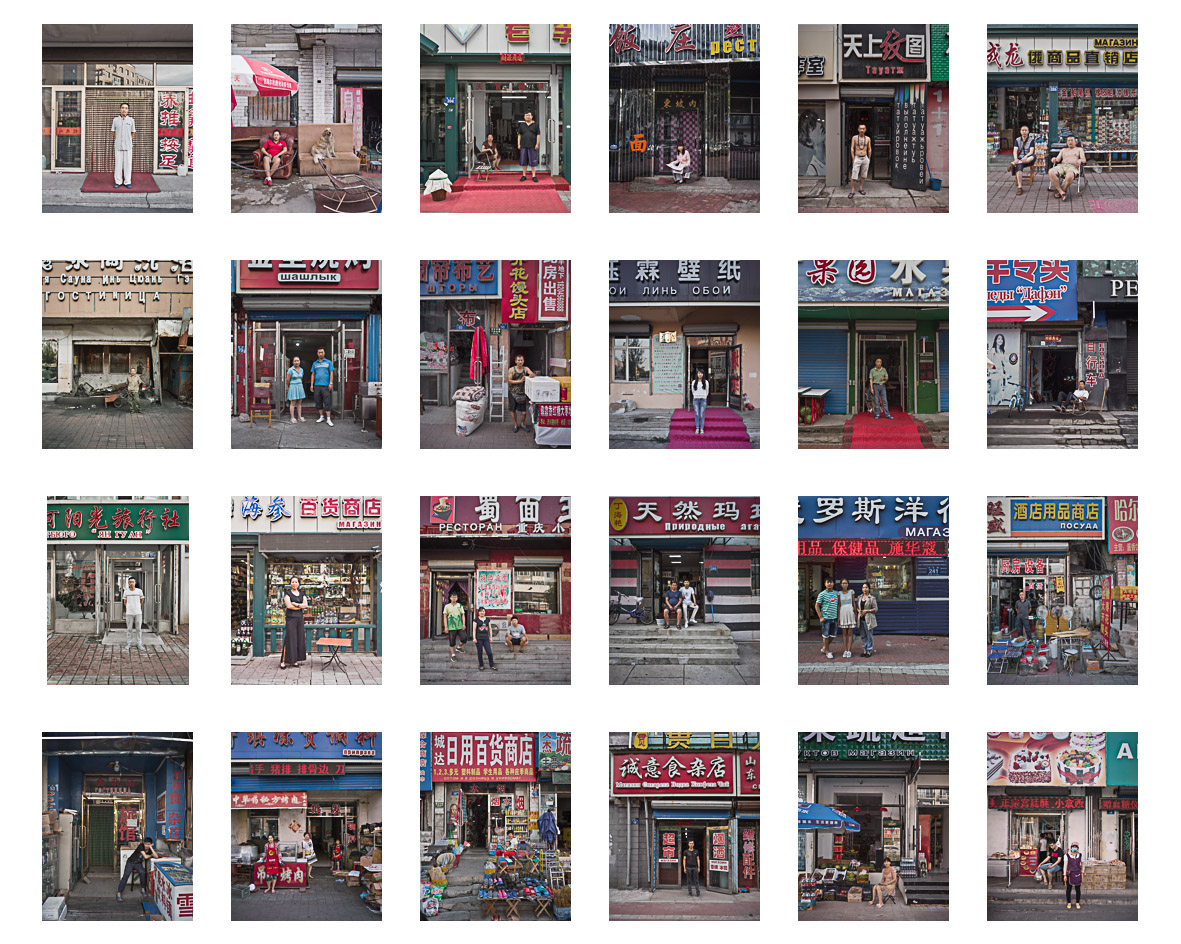

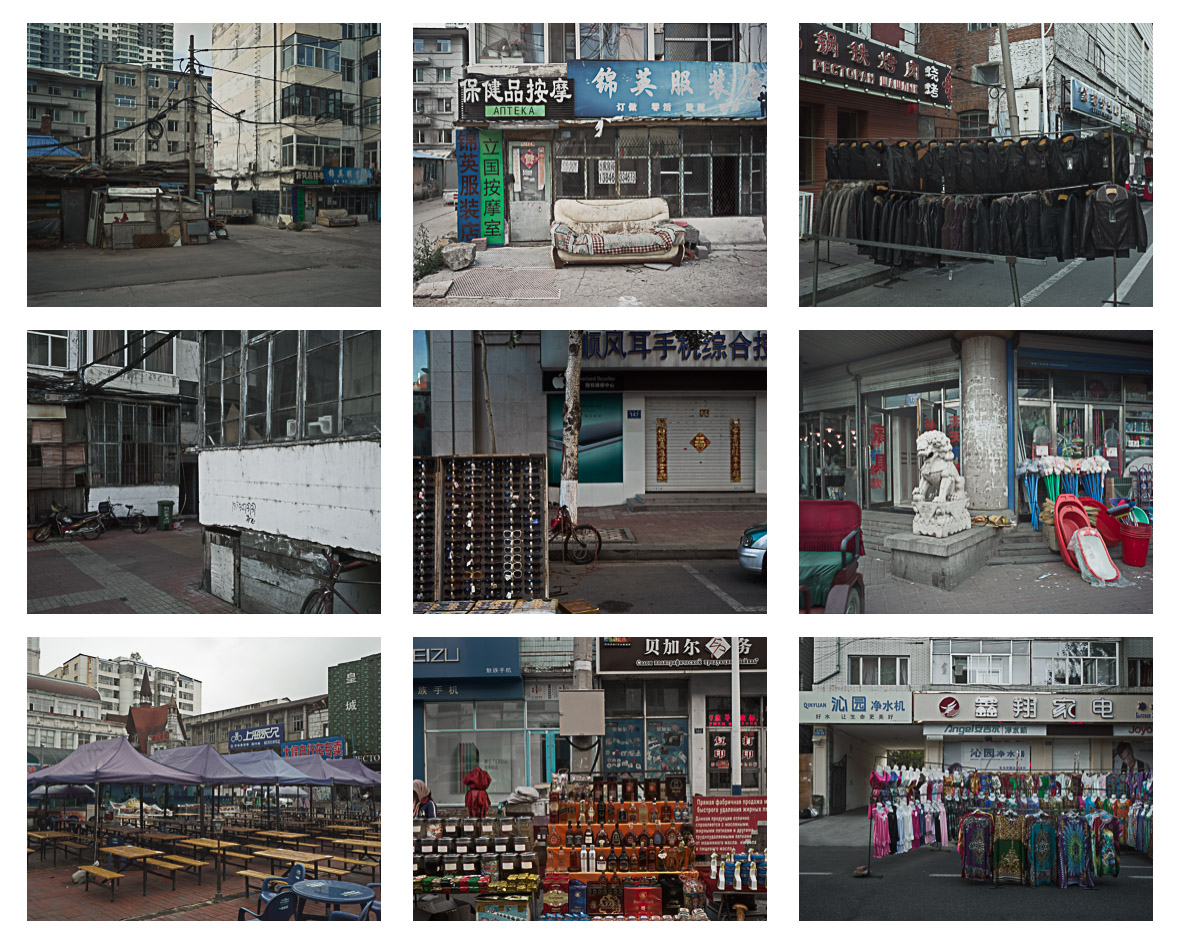

It takes a brave man to jump off a moving train for the sake of a sale, but the clothes hawkers had the easy courage of men who did this on the regular. I watched as they leapt off the front carriage as the train chugged into a station with no stop, bundles of cheap Chinese jeans and jackets on their arms, exchanged hurried words and cash with waiting Russians, and jumped back on the last carriage as the Trans-Siberian trundled steadily toward Moscow from Ulaanbaatar. They were Mongolians, but they knew enough Russian and Chinese to barter in both languages—and to flirt. After the stop, one of them came into the dining carriage where the Russian waitress, happily plump, danced with him without music, one hand turning in his and the other keeping hold of her cigarette as she moved. “Beautiful!” he said in Russian. They sat down with me, and we established the boundaries of our languages; her expansive, laughing Russian, of which I could get no more than the glimmers and he understood easily but spoke brokenly, their song-and-movie-aided understanding of my English, and the pidgin Chinese he and I shared. (This was in 2006; since then my Chinese has expanded from pidgin into harsh-voiced crow.) “English gentleman!” she said, in English, and laughed. “Chinese gentleman!” she said of the Mongolian, which he didn’t correct, adding, in Russian, what I took from the loanwords to be “Confucian gentleman, correct? Chinese are Confucians, like English are Catholics.” A little later that day, the train pulled in for a short stop, where the bargaining could be fuller and fiercer. Russian traders were waiting in anticipation on the platform, young men and middle-aged women. The men were gopniks—skinheads in shell suits and gold rings, faces hardened by growing up in Russia’s post-apocalyptic 1990s. (Chavs, the English would say; white trash, the Americans.) The Mongolians preferred the women, for good reason. I watched as two of the gopniks argued loudly with a Mongolian. As the train was about to leave, one of them suddenly shoved the Mongolian trader violently to the ground as the other grabbed his bundle of plastic-wrapped clothes. They bolted with the speed of practiced thieves. The Mongolian leapt to his feet, yelled, and drew his knife, drawing it back over his head to throw. The crowd gasped. He threw—and it clattered uselessly on the platform, the blade only half-extended, as the train started pulling out of the station. He grabbed his knife and leapt back into the carriage and the commiserations of his comrades. I decided that if I were the thieves, I would not frequent this route for a while. Trade made the Sino-Russian borderlands, carving a great path across Eurasia. It still shaped people’s lives: my usual driver in Mongolia, “Jack,” had bought his taxi with money earned from shuttling cars from Moscow to China in the 1990s. He went west by train and returned by road, sleeping wrapped in sheepskins in the old junkers he bought. In Budapest, my cosmopolitan grandfather Rudi Fischer walked me to a favorite haunt of his, the “Chinese Market” in Jozsefvaros, one of many grand bazaars of cheap goods shuttled through Russia to Eastern Europe, full of gaming and noodles. In the small Russian segment of Beijing around Jianguomen, every third building was labeled “KARGO.” But the threads of friendship forged along the route, sometimes cautious, sometimes full-throated or loving, were often snapped by violence. Sometimes this was sporadic, and local; more often it was a product of the frictions between two great empires, the Russians and the Chinese, whose resemblances to each other had a magnetic quality, alternately attracting and repelling. And once, it came close to ending the world.

James Palmer - China File January 18, 2016

Editor: David Barrera